Merrick tvc-7 Read online

Page 9

These words saddened and disturbed me.

"The Everlasting has not fixed his canon against my self-slaughter," he said, paraphrasing Shakespeare, "because all I need do to accomplish it is not seek shelter at the rising of the sun. I dream she may warn me of hellfires and of the need for repentance. But then, this is a little miracle play, isn't it? If she comes, she may be groping in darkness. She may be lost among the wandering dead souls whom Lestat saw when he traveled out of this world."

"Absolutely anything is possible," I answered.

A long interval occurred during which I went quietly up to him and laid my hand on his shoulder, to let him know in my way that I respected his pain. He didn't acknowledge this tiny intimacy. I made my way back to the sofa and I waited. I had no intention of leaving him with such thoughts in his mind.

At last he turned around.

"Wait here," he said quietly, and then he went out of the room and down the passage. I heard him open a door. Within a brief moment he was back again with what appeared to be a small antique photograph in his hand.

I was immensely excited. Could it be what I thought?

I recognized the small black gutter perche case into which it was fitted, so like the ones that framed the daguerreotypes belonging to Merrick. It appeared intricate and well preserved.

He opened the case and looked at the image, and then he spoke:

"You mentioned those family photographs of our dearly beloved witch," he said reverently. "You asked if they were not vehicles for guardian souls."

"Yes, I did. As I told you, I could have sworn those little pictures were looking at Aaron and at me."

"And you mentioned that you could not imagine what it had meant to us to see daguerreotypes—or whatever they might be called—for the first time so many years ago."

I was filled with a sort of amazement as I listened to him. He had been there. He had been alive and a witness. He had moved from the world of painted portraits to that of photographic images. He had drifted through those decades and was alive now in our time.

"Think of mirrors," he said, "to which everyone is accustomed. Think of the reflection suddenly frozen forever. That is how it was. Except the color was gone from it, utterly gone, and there lay the horror, if there was one; but you see, no one thought it was so remarkable, not while it was happening, and then it was so common. We didn't really appreciate such a miracle. It went popular too very fast. And of course when it first started, when they first set up their studios, it was not for us."

"For us?"

"David, it had to be done in daylight, don't you see? The first photographs belonged to mortals alone."

"Of course, I didn't even think of it."

"She hated it," he said. He looked again at the image. "And one night, unbeknownst to me, she broke the lock of one of the new studios—and there were many of them—and she stole all the pictures she could find. She broke them, smashed them in a fury. She said it was ghastly that we couldn't have our pictures made. 'Yes, we see ourselves in mirrors, and old tales would have it not,' she screamed at me. 'But what about this mirror? Is this not some threat of judgment?' I told her absolutely it was not.

"I remember Lestat laughed at her. He said she was greedy and foolish and ought to be happy with what she had. She was past all tolerance of him, and didn't even answer him. That's when he had the miniature painted of her for his locket, the locket you found for him in a Talamasca vault."

"I see," I answered. "Lestat never told me such a story."

"Lestat forgets many things," he said thoughtfully and without judgment. "He had other portraits of her painted after that. There was a large one here, very beautiful. We took it with us to Europe. We took trunks of our belongings, but that time I don't want to remember. I don't want to remember how she tried to hurt Lestat."

I was silent out of respect.

"But the photographs, the daguerreotypes, that's what she wanted, the real image of herself on glass. She was furious, as I told you. But then years later, when we reached Paris, in those lovely nights before we ever happened upon the Theatre des Vampires and the monsters who would destroy her, she found that the magic pictures could be taken at night, with artificial light!"

He seemed to be reliving the experience painfully, I remained quiet.

"You can't imagine her excitement. She had seen an exhibit by the famous photographer Nadar of pictures from the Paris catacombs. Pictures of cartloads of human bones. Nadar was quite the man, as I'm sure you know. She was thrilled by the pictures. She went to his studio, by special appointment, in the evening, and there this picture was made."

He came towards me.

"It's a dim picture. It took an age for all the mirrors and the artificial lamps to do their work. And Claudia stood still for so long, well, only a vampire child might have worked such a trick. But she was very pleased with it. She kept it on her dressing table in the Hotel Saint-Gabriel, the last place that we ever called our home. We had such lovely rooms there. It was near to the Opera. I don't think she ever unpacked the painted portraits. It was this that mattered to her. I'd actually thought she would come to be happy in Paris. Maybe she would have been ... But there wasn't time. This little picture, she felt it was only the beginning, and planned to return to Nadar with an even lovelier dress."

He looked at me.

I stood up to receive the picture, and he placed it in my hands most carefully, as though it were about to shatter of its own accord.

I was dumbfounded. How small and innocent she seemed, this irretrievable child of fair locks and chubby cheeks, of darkened Cupid's bow lips and white lace. Her eyes veritably blazed from the shadowy glass as I looked at her. And there came back that very suspicion of years ago, that I'd suffered so strongly with Merrick's pictures, that the image was gazing at me.

I must have made some small sound. I don't know. I shut the little case. I even worked the tiny gold clasp into the lock.

"Wasn't she beautiful?" he asked. "Tell me. It's past a matter of opinion, isn't it? She was beautiful. One cannot deny that simple fact."

I looked at him, and I wanted to say that she was, indeed she was, she was lovely, but no sound would come out of my mouth.

"We have this," he said, "for Merrick's magic. Not her blood, nor an article of clothing, nor a lock of hair. But we have this. After her death, I went back to the hotel rooms where we'd been happy and I retrieved it, and all the rest I left."

He opened his coat and slipped the picture into his breast pocket. He looked a little shocked, his eyes purposefully blank, and then he gave a little shake of the head.

"Don't you think it will be powerful for the magic?" he asked.

"Yes," I said. There were so many comforting words tumbling through my mind, but all seemed poor and stiff.

We stood looking at one another, and I was surprised at the feeling in his expression. He seemed altogether human and passionate. I could scarce believe the despair with which he endured.

"I don't really want to see her, David," he said. "You must believe me on that score. I don't want to raise her ghost, and frankly, I don't think we can."

"I believe you, Louis," I said.

"But if she does come, and she is in torment. . ."

"Then Merrick will know how to guide her," I said quickly. "I'll know how to guide her. All mediums in the Talamasca know how to guide such spirits. All mediums know to urge such spirits to seek the light."

He nodded. "I was counting on it," he said. "But you see, I don't think Claudia would ever be lost, only wanting to remain. And then, it might take a powerful witch like Merrick to do the convincing that beyond this pale there lies an end to pain."

"Precisely," I said.

"Well, I've troubled you enough for one evening," he said. "I have to go out now. I know that Lestat is uptown in the old orphanage. He's listening to his music there. I want to make certain that no intruders have come in."

I knew this was fanciful. Lestat, regardless of

his frame of mind, could defend himself against almost anything, but I tried to accept the words as a gentleman should.

"I'm thirsting," he added, glancing at me, with just the trace of a smile. "You're right on that account. I'm not really going to see to Lestat. I've already been to St. Elizabeth's. Lestat is alone with his music as he chooses to be. I'm thirsting very much. I'm going to feed. And I have to go about it alone."

"No," I said softly. "Let me go with you. After Merrick's spell, I don't want you to go alone."

This was most decidedly not Louis's way of doing things; however, he agreed.

6

WE WENT OUT TOGETHER, walking quite rapidly until we were well away from the lighted blocks of the Rue Bourbon and the Rue Royale.

New Orleans soon opened up her underbelly to us, and we went deep into a ruined neighborhood, not unlike the neighborhood in which I'd long ago met Merrick's Great Nananne. But if there were any great witches about, I found no hint of them on this night.

Now, let me say here a few words about New Orleans and what it was to us.

First and foremost it is not a monstrous city like Los Angeles or New York. And even though it has a sizable underclass of dangerous individuals, it is, nevertheless, a small place.

It cannot really support the thirst of three vampires. And when great numbers of blood drinkers are drawn to it, the random blood lust creates an unwanted stir.

Such had recently happened, due to Lestat publishing his memoirs of Memnoch the Devil, during which time many of the very ancient came to New Orleans, as well as rogue vampires—creatures of powerful appetite and little regard for the species and the subterranean paths which it must follow to survive in the modern world.

During that time of coming together, I had managed to persuade Armand to dictate his life story to me; and I had circulated, with her permission, the pages which the vampire Pandora had given me sometime before.

These stories attracted even more of the maverick blood drinkers—those creatures who, being masterless and giving out lies as to their beginnings, often taunt their mortal prey and seek to bully them in a way that can only lead to trouble for all of us.

The uneasy convocation did not last long.

But though Marius, a child of two millennia, and his consort, the lovely Pandora, disapproved of the young blood drinkers, they would not lift a hand against them to put them to death or to flight. It was not in their nature to respond to such a catastrophe, though they were outraged by the conduct of these baseborn fiends.

As for Lestat's mother, Gabrielle, one of the coldest and most fascinating individuals whom I have ever encountered, it was of absolutely no concern to her at all, as long as no one harmed her son.

Well, it was quite impossible for anyone to harm her son. He is unharmable, as far as we all know. Or rather, to speak more plainly, let me say that his own adventures have harmed Lestat far more than any vampire might. His trip to Heaven and Hell with Memnoch, be it delusion or supernatural journey, has left him stunned spiritually to such a point that he is not ready to resume his antics and become the Brat Prince whom we once adored.

However, with vicious and sordid blood drinkers breaking down the very doors of St. Elizabeth's and coming up the iron stairs of our very own town house in the Rue Royale, it was Armand who was able to rouse Lestat and goad him into taking the situation in hand.

Lestat, having already waked to listen to the piano music of a fledgling vampire, blamed himself for the tawdry invasion. It was he who had created the "Coven of the Articulate," as we had come to be called. And so, he declared to us in a hushed voice, with little or no enthusiasm for the battle, that he would put things right.

Armand—given in the past to leading covens, and to destroying them—assisted Lestat in a massacre of the unwelcome rogue vampires before the social fabric was fatally breached.

Having the gift of fire, as the others called it—that is, the means to kindle a blaze telekinetically—Lestat destroyed with flames the brash invaders of his own lair, and all those who had violated the privacy of the more retiring Marius and Pandora, Santino, and Louis and myself. Armand dismembered and obliterated those who died at his hand.

Those few preternatural beings who weren't killed fled the city, and indeed many were overtaken by Armand, who showed no mercy whatsoever to the misbegotten, the heartlessly careless, and the deliberately cruel.

After that, when it was plain to one and all that Lestat had returned to his semi-sleep, absorbed utterly in recordings of the finest music provided for him by me and by Louis, the elders—Marius, Pandora, Santino, and Armand, with two younger companions—gradually went their way.

It was an inevitable thing, that parting, because none of us could really endure the company of so many fellow blood drinkers for very long.

As it is with God and Satan, humankind is our subject matter. And so it is that, deep within the mortal world and its many complexities, we choose to spend our time.

Of course, we will all come together at various times in the future. We know well how to reach one another. We are not above writing letters. Or other means of communication. The eldest know telepathically when things have gone terribly wrong with the young ones, and vice versa. But for now, only Louis and Lestat and I hunt the streets of New Orleans, and so it will be for some time.

That means, strictly speaking, that only Louis and I hunt, for Lestat simply does not feed at all. Having the body of a god, he has subsumed the lust which still plagues the most powerful, and lies in his torpor as the music plays on.

And so New Orleans, in all her drowsy beauty, is host to only two of the Undead. Nevertheless, we must be very clever. We must cover up the deeds that we do. To feed upon the evildoer, as Marius has always called it, is our vow; however, the blood thirst is a terrible thing.

But before I return to my tale—of how Louis and I went out on this particular evening, allow me a few more words about Lestat.

I personally do not think that things are as simple with him as the others tend to believe. Above, I have given you pretty much "the party line," as the expression goes, as to his coma-like slumber and his music. But there are very troubling aspects to his presence which I cannot deny or resolve.

Unable to read his mind, because he made me a vampire and I am therefore his fledgling and far too close to him for such communication, I, nevertheless, perceive certain things about him as he lies by the hour listening to the brilliant and stormy music of Beethoven, Brahms, Bach, Chopin, Verdi, and Tchaikovsky, and the other composers he loves.

I've confessed these "doubts" about his well-being to Marius and to Pandora and to Armand. But no one of them could penetrate the veil of preternatural silence which he has drawn about his entire being, body and soul.

"He's weary," say the others. "He'll be himself soon." And "He'll come around."

I don't doubt these things. Not at all. But to put it plainly, something is more wrong with him than anyone has guessed. There are times when he is not there in his body.

Now this may mean that he is projecting his soul up and out of his body in order to roam about, in pure spirit form, at will. Certainly Lestat knows how to do this. He learnt it from the most ancient of the vampires; and he proved that he could do it, when with the evil Body Thief he worked a switch.

But Lestat does not like that power. And no one who has had his body stolen is likely to use it for more than a very short interval in any one night.

I feel something far more grave is wrong there, that Lestat is not always in control of either body or soul, and we must wait to discover the terms and outcome of a battle which might still be going on.

As for Lestat's appearance, he lies on the Chapel floor, or on the four-poster bed in the town house, with his eyes open, though they appear to see nothing. And for a while after the great cleansing battle, he did periodically change his clothes, favoring the red velvet jackets of old, and his lace-trimmed shirts of heavy linen, along with slim pants and plain b

lack boots.

Others have seen this attention to wardrobe as a good sign. I believe Lestat did these things so that we would leave him alone.

Alas, I have no more to say on the subject in this narrative. At least I don't think so. I can't protect Lestat from what is happening, and no one really has ever succeeded in protecting him or stopping him, no matter what the circumstances of his distress.

Now, let me return to my record of events.

Louis and I had made our way deep into a forlorn and dreadful part of the city where many houses stood abandoned, and those few which still showed evidence of habitation were locked up tight with iron bars upon their windows and doors.

As always happens with any neighborhood in New Orleans, we came within a few blocks to a market street, and there we found many desolate shops which had long ago been shut up with nails and boards. Only a "pleasure club," as it was called, showed signs of habitation and those inside were drunk and gambling the night away at card games and dice.

However, as we continued on our journey, I following Louis, as this was Louis's hunt, we soon came to a small dwelling nestled between the old storefronts, the ruins of a simple shotgun house, whose front steps were lost in the high weeds.

There were mortals inside, I sensed it immediately, and they were of varying dispositions.

The first mind which made itself known to me was that of an aged woman, keeping watch over a cheap little bassinet with a baby inside of it, a woman who was actively praying that God deliver her from her circumstances, those circumstances pertaining to two young people in a front room of the house who were entirely given over to drink and drugs.

In a quiet and efficient manner, Louis led the way back to the overgrown alley to the rear of this crooked little shack, and without a sound he peered through the small window, above a humming air conditioner, at the distraught woman, who wiped the face of the infant, who did not cry.

Again and again I heard this woman murmur aloud that she didn't know what she would do with those young people in the front room, that they had destroyed her house and home and left her this miserable little infant who would starve to death or die of other neglect if the young mother, drunk and dissolute, was forced to care for the child alone.

Interview with the Vampire

Interview with the Vampire Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt

Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt The Queen Of The Damned

The Queen Of The Damned The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty

The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty Prince Lestat

Prince Lestat The Master of Rampling Gate

The Master of Rampling Gate The Vampire Lestat

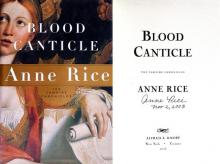

The Vampire Lestat Blood Canticle

Blood Canticle Beauty's Release

Beauty's Release Pandora

Pandora Servant of the Bones

Servant of the Bones Of Love and Evil

Of Love and Evil Beauty's Punishment

Beauty's Punishment Cry to Heaven

Cry to Heaven The Tale of the Body Thief

The Tale of the Body Thief The Witching Hour

The Witching Hour Memnoch the Devil

Memnoch the Devil Blackwood Farm

Blackwood Farm Beauty's Kingdom

Beauty's Kingdom Belinda

Belinda Lasher

Lasher Vittorio, the Vampire

Vittorio, the Vampire Angel Time

Angel Time Called Out of Darkness: A Spiritual Confession

Called Out of Darkness: A Spiritual Confession Blood And Gold

Blood And Gold The Passion of Cleopatra

The Passion of Cleopatra Taltos

Taltos Exit to Eden

Exit to Eden Blood Communion (The Vampire Chronicles #13)

Blood Communion (The Vampire Chronicles #13) The Wolf Gift

The Wolf Gift The Wolves of Midwinter

The Wolves of Midwinter Prince Lestat and the Realms of Atlantis

Prince Lestat and the Realms of Atlantis The Ultimate Undead

The Ultimate Undead The Vampire Lestat tvc-2

The Vampire Lestat tvc-2 The Road to Cana

The Road to Cana Taltos lotmw-3

Taltos lotmw-3 Merrick tvc-7

Merrick tvc-7 Called Out of Darkness

Called Out of Darkness Pandora - New Vampires 01

Pandora - New Vampires 01 Bllod and Gold

Bllod and Gold The Queen Of the Damned: Vampire Chronicles

The Queen Of the Damned: Vampire Chronicles The Sleeping Beauty Trilogy

The Sleeping Beauty Trilogy The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty b-1

The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty b-1 Lasher lotmw-2

Lasher lotmw-2 The Tale of the Body Thief tvc-4

The Tale of the Body Thief tvc-4 The Vampire Chronicles Collection

The Vampire Chronicles Collection Ramses the Damned

Ramses the Damned The Mummy - or Ramses the Damned

The Mummy - or Ramses the Damned Vittorio, The Vampire - New Vampires 02

Vittorio, The Vampire - New Vampires 02 The Vampire Armand tvc-6

The Vampire Armand tvc-6 Queen of the Damned tvc-3

Queen of the Damned tvc-3 The witching hour lotmw-1

The witching hour lotmw-1 Feast of All Saints

Feast of All Saints Queen of the Damned

Queen of the Damned The Wolves of Midwinter twgc-2

The Wolves of Midwinter twgc-2 The Mummy

The Mummy Blood and Gold tvc-8

Blood and Gold tvc-8 Blood Communion

Blood Communion Interview with the Vampire tvc-1

Interview with the Vampire tvc-1 Prince Lestat: The Vampire Chronicles

Prince Lestat: The Vampire Chronicles