Bllod and Gold Read online

Page 27

At last the Cloud Gift came to me. I needn't climb the slope to the vault any longer. I had only to will myself to rise from the road and I stood before the hidden doors to the passage. It was frightening, yet I loved it for I could travel even greater distances when I had the strength for it, which was less often as time went on.

Meantime castles and monasteries had come to appear in this land which had once been the territory of warring barbarian tribes. With the Cloud Gift I could visit the high peaks upon which these marvelous structures were created and sometimes slip into their very rooms.

I was a drifter through eternity, a spy among other hearts. I was a blood thing who knew nothing about death and finally nothing about time.

Sometimes on the winds I drifted. Always through the lives of others I drifted. And in the mountain vault I did my usual painting for Those Who Must Be Kept, covering their walls this time with old Egyptians come to make sacrifice, and I kept my few books there that comforted my soul.

In the monasteries I often spied upon the monks. I loved to watch them writing in their scriptoriums, and it was a comfort to me to see that they kept the old Greek and Roman poetry safe. In the small hours, I went into the libraries, and there, a hooded figure, hunched over the lectern, I read the old poetry and history from my time.

Never was I discovered. I was far too clever. And often I lingered outside the chapel in the evening, listening to the plainsong of the monks, which created a peace inside of me, rather like walking the cloisters, or listening to the steeple bells.

Meantime the art of Greece and Rome which I had loved so much completely died away. A dour religious art took its place. Proportion and naturalism were no longer important. What mattered was that those images which were rendered be evocative of devotion to God.

Human figures in paintings or in stone were often impossibly gaunt, with bold staring eyes. A dreadful grotesquery reigned. It was not for want of knowledge, or skill, for manuscripts were decorated with tremendous patience, and monasteries and churches were built at great cost. Those who made this art could have made anything. It was a choice. Art was not to be sensual. Art was to be pious. Art was to be grim. And so the classical world was lost.

Of course I found wonders in this new world, I cannot deny it. Using the Cloud Gift, I traveled to the great Gothic cathedrals, whose high arches surpassed anything I'd ever beheld. I was stunned by the beauty of these cathedrals. I marveled at the market towns which were growing up all over Europe. It seemed that commerce and crafts had settled the land which war could not settle alone.

New languages were spoken everywhere. French was the language of the elite. But there was English and German and Italian as well.

I saw it all happening, and yet I saw nothing. And then finally, perhaps in the year 1200—I am uncertain—I lay down in the vault for a long sleep.

I was weary of the world and quite impossibly strong. I confessed my intentions to Those Who Must Be Kept. The lamps would eventually

burn down, I told them. And there would only be darkness, but please, would they forgive me. I was tired. I wanted to sleep for a long, long time.

As I slept, I learnt. My preternatural hearing was too strong now for me to lie in silence. I could not escape the voices of those who cried out, be they blood drinkers or humans. I could not escape the drifting history of the world.

And so it was with me in the high Alpine pass where I was hidden. I heard the prayers of Italy. I heard the prayers of Gaul which had now become the country known as France.

I heard the souls suffering the terrible disease of the thirteen

hundreds known now most appropriately as the Black Death.

In the darkness I opened my eyes. I listened. Perhaps I even studied.

And then finally I roused myself and went down into Italy, afraid for the fate of all the world. I had to see the land I loved with my own eyes. I had to go back.

The city that drew me was one I had not known before in my life. It was a new city, in that it had not existed in the ancient time of the Caesars, and was now a great port. In fact, it was very likely the greatest city of all Europe. Venice was the name of it, and the Black Death had come to it by way of the ships in its harbor, and thousands were

desperately sick.

Never had I visited it before. It would have been too painful, and now as I came into Venice, I found it a city of gorgeous palaces built upon dark green canals. But the Black Death had ahold of the populace who were dying in huge numbers daily, and ferries were taking the bodies out to be buried deeply in the soil of the islands in the city's immense lagoon.

Everywhere there was weeping and desolation. People gathered together to die in sickrooms, faces covered in sweat, bodies tormented by incurable swellings. The stench of the dead rose everywhere. Some were trying to flee the city and its infestation. Others remained with their suffering loved ones.

Never had I seen such a plague. And yet it was amid a city of such remarkable splendor, I found myself numb with sorrow and tantalized by the beauty of the palaces, and by the wonder of the Church of San Marco which bore exquisite testament to the city's ties with Byzantium to which it sent its many merchant ships.

I could do nothing but weep in such a place. It was no time for peering by torchlight at paintings or statues that were wholly new to me. I had to depart, out of respect for the dying, no matter what I was.

And so I made my way South to another city which I had not known in my mortal life, the city of Florence in the heart of Tuscany, a

beautiful and fertile land.

Understand, I was avoiding Rome at this point. I could not bear to see my home, once more in ruin and misery. I could not see Rome

visited by this plague.

So Florence was my choice, as I have said—a city new to me, and prosperous, though not as rich as Venice perhaps, and not as beautiful, though full of huge palaces and paved streets.

And what did I find, but the same dreadful pestilence. Vicious bullies

demanded payment to remove the bodies, often beating the dying or those who tried to tend them. Six to eight corpses lay at the doors of various houses. The priests came and went by torchlight, trying to give the Last Rites. And everywhere the same stench as in Venice, the stench that says all is coming to an end.

Weary and miserable, I made my way into a church, somewhere near the center of Florence, though I cannot say what church it was, and I stood against the wall, gazing at the distant tabernacle by candlelight, wondering as so many praying mortals wondered: What would become of this world?

I had seen Christians persecuted; I had seen barbarians sack cities; I had seen East and West quarrel and finally break with each other; I had seen Islamic soldiers waging their holy war against the infidel; and now I had seen this disease which was moving all through the world.

And such a world, for surely it had changed since the year when I had fled Constantinople. The cities of Europe had grown full and rich as flowers. The barbarian hordes had become settled people. Byzantium still held the cities of the East together.

And now this dreadful scourge—this plague.

Why had I remained alive, I wondered? Why must I endure as the witness to all these many tragic and wonderful things? What was I to make of what I beheld?

And yet, even in my sorrow, I found the church beautiful with its myriad lighted candles, and spying a bit of color far ahead of me, in one of the chapels to the right side of the high altar, I made my way towards it, knowing full well that I would find rich paintings there, for I could see something of them already.

None of those ardently praying in the church took any notice of me, a single being in a red velvet hooded cloak, moving silently and swiftly to the open chapel so that I might see what was painted there.

Oh, if only the candles had been brighter. If only I had dared to light a torch. But I had the eyes of a blood drinker, didn't I? Why complain? And in this chapel I saw painted figures unlike any I had seen bef

ore. They were religious, yes, and they were severe, yes, and they were pious, yes, but something new had been sparked here, something that one might almost call sublime.

A mixture of elements had been forged. And I felt a great joy even in my sorrow, until I heard a low voice behind me, a mortal voice. It was speaking so softly that I doubt another mortal would even have heard.

"He's dead," said the mortal. "They're all dead, all the painters who did this work."

I was shocked with pain.

"The plague took them," said this man.

He was a hooded figure as I was, only his cloak was of a dark color, and he looked at me with bright feverish eyes.

"Don't fear," he said. "I've suffered it and it hasn't killed me and I can't pass it on, don't you see? But they're all dead, those painters. They're gone. The plague's taken them and all they knew."

"And you? " I asked. "Are you a painter? "

He nodded. "They were my teachers," he said as he gestured towards the walls. "This is our work, unfinished," he said. "I can't do it alone."

"You must do it," I said. I reached into my purse. I took out several gold coins, and I gave them to him.

"You think this will help?" he asked, dejectedly.

"It's all I have to give," I said. "Maybe it can buy you privacy and quiet. And you can begin to paint again."

I turned to go.

"Don't leave me," he said suddenly.

I turned around and looked at him. His gaze was level with mine and very insistent.

"Everyone's dying and you and I are not dying," he said. "Don't go. Come with me, have a drink of wine with me. Stay with me."

"I can't," I said. I was trembling. I was too charmed by him, much too much. I was so close to killing him. "I would stay with you if I could," I said.

And then I left the city of Florence, and I returned to the vault of Those Who Must Be Kept.

I lay down again for a long sleep, feeling the coward that I had not gone to Rome, and thankful that I had not drunk dry the blood of the exquisite soul who had approached me in the church.

But something had been forever changed in me.

In the church in Florence I had glimpsed new paintings. I had glimpsed something which filled me with hope.

Let the plague run its course, I prayed, and I closed my eyes.

And the plague did finally die out.

All the voices of Europe sang.

They sang of the new cities, and great victories, and terrible defeats. Everything in Europe was being transformed. Commerce and prosperity bred art and culture, as the royal courts and cathedrals and monasteries of the recent past had done.

They sang of a man named Gutenberg in the city of Mainz who had invented a printing press which could make cheap books by the

hundreds. Common people could own their own copies of Sacred Scripture, books of the Holy Hours, books of comic stories and pretty poems. All over Europe new printing presses were being built.

They sang of the tragic fall of Constantinople to the invincible Turkish army. But the proud cities of the West no longer depended upon the far-away Greek Empire to protect them. The lament for Constantinople went unheeded.

Italy, my Italy, was illuminated by the glory of Venice and Florence and Rome.

It was time now for me to leave this vault.

I roused myself from my excited dreams.

It was time for me to see this world which marked its time as the year after Christ 1482.

Why I chose that year I am uncertain except perhaps that the voices of Venice and Florence called me most eloquently, and I had earlier beheld these cities in their tribulation and grief. I wanted desperately to see them in their splendor.

But I must go home first, all the way South to Rome.

So lighting the oil lamps once more for my beloved Parents, wiping the dust from their ornaments and their fragile robes, praying to them as I always did, I took my leave to enter one of the most exciting times which the Western world had ever seen.

14

I WENT TO ROME. I could settle for nothing less. What I found there was to sting my heart, but also to astonish me. It was an enormous and busy city, determined to rise from layers upon layers of ruin, full of merchants and craftsmen hard at work on grand palaces for the Pope and his Cardinals and for other rich men.

The old Forum and Colosseum were still standing, indeed there were many many recognizable ruins of Imperial Rome—including the Arch of Constantine—but blocks of ancient stone were constantly being pilfered for new buildings. However scholars were everywhere studying these ruins, and many argued for their maintenance as they were.

Indeed the whole thrust of the age was to preserve the remnants of the ancient times in which I'd been born, and indeed to learn from them, and imitate the art and the poetry, and the vigor of this

movement surpassed my wildest dreams.

How can I say it more lucidly? This prosperous era, given over to trade and banking, in which so many thousands wore thick and beautiful clothes of velvet, had fallen in love with the beauty of ancient Rome and Greece!

Never had I thought such a reversal would occur as I had lain in my vault during the weary centuries, and I was at first too exhilarated by all I saw to do much but walk about the muddy streets, accosting mortals with as much graciousness as I could muster, asking them questions about what was going on about them, and what they thought of the times in which they lived.

Of course I spoke the new language, Italian, which had grown up from the old Latin, and I soon became used to it on my ears and on my tongue. It wasn't such a bad language. Indeed it was beautiful, though I quickly learnt that scholars were well versed in their Latin and Greek.

Out of a multitude of answers to my questions I also learnt that Florence and Venice were deemed to be far ahead of Rome in their spiritual rebirth, but if the Pope were to have his way that was soon to change.

The Pope was no longer only a Christian ruler. He had made up his mind that Rome must be a true cultural and artistic capital, and not only was he completing work upon the new St. Peter's Basilica but he was working as well upon the Sistine Chapel, a great enterprise within his palatial walls.

Artists had been brought from Florence for some of this painting, and the city was much intrigued as to the merits of the frescoes which had been done.

I spent as much time as I could in the streets and in the taverns listening to gossip of all this, and then I made for the Papal Palace determined to see the Sistine Chapel for myself.

What a fateful night this was for me.

In all the dark centuries since I had left my beloved Zenobia and Avicus, I had had my heart stolen by various mortals and various works of art, but nothing I had experienced could quite prepare me for what I was to see when I entered the Sistine Chapel.

Understand, I do not speak of Michelangelo, so well known to all the world for his work there, for Michelangelo was but a child at this time. And his works in the Sistine Chapel were yet to come.

No, it was not the work of Michelangelo that I saw on this fateful night. Put Michelangelo out of your thoughts.

It was the work of someone else.

Getting by the palace guards easily enough, I quickly found myself within the great rectangle of this august chapel, which though not open to the public at large was destined to be used for high ceremonials

whenever it should be complete.

And what caught my eye immediately among any number of frescoes was an enormous one filled with brilliantly painted figures, all involving, it seemed, the same dignified elder with golden light streaming from his head as he appeared with three different groupings of those who responded to his command.

Nothing had prepared me for the naturalism with which the multitudinous figures were painted, the vivid yet dignified expressions on the faces of the people, and the gracefully draped garments with which the beings were clothed.

There was great turbulence among these three exquisitely ren

dered groups of persons as the white-haired figure with the gold light streaming from his head instructed them or upbraided them or

corrected them, his own face quite seemingly stern and calm.

All existed in a harmony such as I could never have imagined, and though their creation alone seemed enough to guarantee that this painting should be a masterpiece there was beyond the figures a

marvelous depiction of an extravagant wilderness and an indifferent world.

Two great ships of the present period were anchored in the faraway

harbor, and beyond the ships there loomed layers of mountains beneath a rich blue sky, and to the right there stood the very Arch of Constantine which still stood in Rome to this day, finely detailed in gold as if it had never been ruined, and the columns of another Roman building, once splendid, now a fragment standing high and proud, though a dark castle loomed beyond.

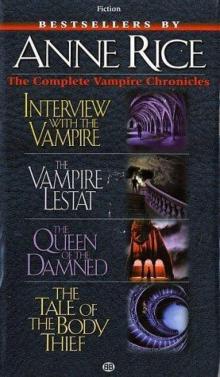

Interview with the Vampire

Interview with the Vampire Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt

Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt The Queen Of The Damned

The Queen Of The Damned The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty

The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty Prince Lestat

Prince Lestat The Master of Rampling Gate

The Master of Rampling Gate The Vampire Lestat

The Vampire Lestat Blood Canticle

Blood Canticle Beauty's Release

Beauty's Release Pandora

Pandora Servant of the Bones

Servant of the Bones Of Love and Evil

Of Love and Evil Beauty's Punishment

Beauty's Punishment Cry to Heaven

Cry to Heaven The Tale of the Body Thief

The Tale of the Body Thief The Witching Hour

The Witching Hour Memnoch the Devil

Memnoch the Devil Blackwood Farm

Blackwood Farm Beauty's Kingdom

Beauty's Kingdom Belinda

Belinda Lasher

Lasher Vittorio, the Vampire

Vittorio, the Vampire Angel Time

Angel Time Called Out of Darkness: A Spiritual Confession

Called Out of Darkness: A Spiritual Confession Blood And Gold

Blood And Gold The Passion of Cleopatra

The Passion of Cleopatra Taltos

Taltos Exit to Eden

Exit to Eden Blood Communion (The Vampire Chronicles #13)

Blood Communion (The Vampire Chronicles #13) The Wolf Gift

The Wolf Gift The Wolves of Midwinter

The Wolves of Midwinter Prince Lestat and the Realms of Atlantis

Prince Lestat and the Realms of Atlantis The Ultimate Undead

The Ultimate Undead The Vampire Lestat tvc-2

The Vampire Lestat tvc-2 The Road to Cana

The Road to Cana Taltos lotmw-3

Taltos lotmw-3 Merrick tvc-7

Merrick tvc-7 Called Out of Darkness

Called Out of Darkness Pandora - New Vampires 01

Pandora - New Vampires 01 Bllod and Gold

Bllod and Gold The Queen Of the Damned: Vampire Chronicles

The Queen Of the Damned: Vampire Chronicles The Sleeping Beauty Trilogy

The Sleeping Beauty Trilogy The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty b-1

The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty b-1 Lasher lotmw-2

Lasher lotmw-2 The Tale of the Body Thief tvc-4

The Tale of the Body Thief tvc-4 The Vampire Chronicles Collection

The Vampire Chronicles Collection Ramses the Damned

Ramses the Damned The Mummy - or Ramses the Damned

The Mummy - or Ramses the Damned Vittorio, The Vampire - New Vampires 02

Vittorio, The Vampire - New Vampires 02 The Vampire Armand tvc-6

The Vampire Armand tvc-6 Queen of the Damned tvc-3

Queen of the Damned tvc-3 The witching hour lotmw-1

The witching hour lotmw-1 Feast of All Saints

Feast of All Saints Queen of the Damned

Queen of the Damned The Wolves of Midwinter twgc-2

The Wolves of Midwinter twgc-2 The Mummy

The Mummy Blood and Gold tvc-8

Blood and Gold tvc-8 Blood Communion

Blood Communion Interview with the Vampire tvc-1

Interview with the Vampire tvc-1 Prince Lestat: The Vampire Chronicles

Prince Lestat: The Vampire Chronicles